America is rolling out giant facilities to feed the AI boom. Can Britain compete?

On a former Second World War airbase in Cambridgeshire plans are afoot to construct one of Europe’s largest data centres, providing the computing energy needed to cope with increasingly powerful artificial intelligence technology.

The positioning of the 100-acre scheme, roughly the size of about 75 football pitches, outside the traditional west London data centre heartland is as much to do with power access as its proximity to the advanced computing and research hubs of Oxford and Cambridge.

“The grid capacity in the Slough area and west London area is very constrained, so getting new connec­tions to the grid is very limited,” said Niall Brunker, co-head for the UK at Icona Capital, the investment firm that is part of the joint venture behind the scheme.

The development, which will have a capacity of 330 megawatts, is one of several energy-hungry data centre projects being planned across the UK in the next few years, designed to power the AI boom. American technology giants and private capital are pouring billions into building the facilities.

However, the UK remains far behind the US in its data centre rollout. Total installed compute capacity in North America stands at 20 gigawatts (GW), according to data from Cushman & Wakefield, the real estate services group.

Even after taking into account projects in the pipeline, the capacity in the UK market stood at just 3.6GW at the end of last year.

Higher energy costs and an aged grid put Britain at risk of falling even behind further, industry insiders have warned.

In January, Sir Keir Starmer backed an action plan to make Britain “one of the great AI superpowers” and an “AI maker” rather than an “AI taker”.

Data centres have been designated as critical infrastructure, to be provided with additional protection from cyber­attacks and IT outages in an effort to bolster investor confidence in building the facilities in the UK.

It is the first such designation for almost a decade after defence and space were awarded the status in 2015.

Yet the UK’s data centres are dwarfed by the so-called hyperscale facilities being rolled out in the US.

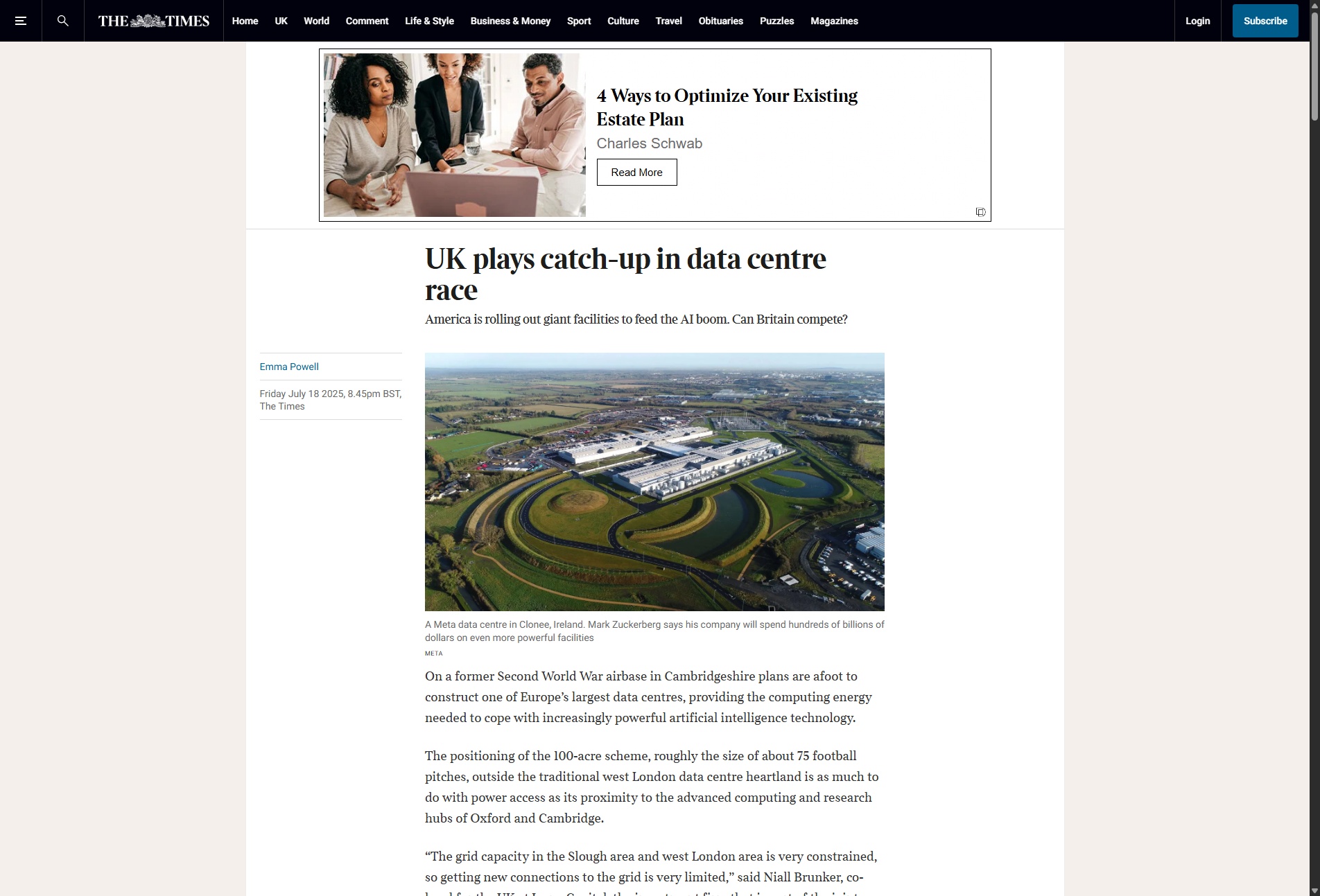

The AI arms race intensified this week after Mark Zuckerberg, the billionaire founder and chief executive of Meta Platforms, said that his company — which owns Facebook, WhatsApp and Instagram — would spend hundreds of billions on rolling out “multi-gigawatt” data centres.

Amazon is planning to build 30 data centres across a vast stretch of farmland in Indiana.

Amazon Web Services, the cloud computing arm of the ecommerce giant, has said it will invest £8 billion in the UK over the next five years on building, operating and maintaining data centres. Google is set to open its first UK data centre in Hertfordshire later this year. Blackstone, the world’s largest private equity firm, plans to spend $10 billion on transforming the site of Britishvolt’s ill-fated attempt to build a gigafactory in Northum­berland.

As demand for the facilities — which are filled with thousands of specialised computer chips required to handle more sophisticated AI workloads — has risen sharply, the land grab for sites in the UK with access to reliable power and water supply has intensified.

Data centres require large amounts of energy to run and keep cool.

“The data centre providers want to make sure they have two good suppliers of power and a good steady source of water, and those are hard to come by in the same place at the same time”, said Alex McMullan, chief international technology officer at Pure Storage, a technology provider that is assisting Meta with its global data centre rollout. “What that really means is we are a little bit behind the curve here.”

A typical AI-focused data centre consumes as much electricity as 100,000 households, but the hyper­scalers under construction will consume 20 times as much, according to the International Energy Agency, which represents member nations of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Develop­ment.

In a report released in November, the national systems operator in the UK projected that demand for electricity to power data centres would grow fourfold by the end of the decade, as requirements from electric vehicles and home heating also rise sharply.

However, the UK’s energy grid is already under pressure. The design and capacity of the nation’s electricity network, which has evolved around coal-fired assets, has failed to keep pace with the rapid expansion of renewables, notably the wind power heavily concentrated in Scotland and on the east coast of England but needs to be delivered to the south of the country.

So-called zombie projects have also led to lengthy grid connection queues, with some projects waiting up to 15 years to connect.

The delays threaten to jeopardise Labour’s aim to rapidly expand the build-out of clean power in an effort to decarbonise the UK’s energy system by the end of the decade./In April, the government put forward plans to reform the grid connection process, prioritising clean energy assets and kicking out the zombie schemes in order to unblock the queue.

In America, Amazon led a $700 million funding round in X-Energy, a nuclear power developer, last year. Microsoft has struck a 20-year power purchase agreement that will bring the Three Mile Island nuclear plant in Pennsylvania back online.

In the UK, nuclear power has dwindled to about 14 per cent of the UK’s electricity mix, down from about a quarter in the late 1990s. Efforts to revive the industry have been drawn out, with Hinkley Point C, the only nuclear power plant currently being built, running years behind and billions of pounds over budget. Small modular reactors, which can be built in a factory and assembled offsite have been put forward as a more expedient option to power data centres, but the first of those is not expected to come online until the mid-2030s.

The power supply issue has become more acute as much of the existing data centre infrastructure predates the AI boom inspired by the breakthrough of ChatGPT in 2022. “We’re already seeing workload demands from a power perspective that are three, four, five times what a data centre has been designed for,” McMullan said.

Britain’s gas distribution networks have claimed that data centre operators are seeking alternatives, having received more than 30 inquiries related to data centre connections in the past six months alone. However, any plans by data centres to connect to Britain’s gas pipelines and build their own gas-fired power plants would threaten to put Britain’s AI ambitions on a collision course with its decarbonisation goals.

The government has said it will create “AI growth zones” where projects have better access to the grid.

These zones will be crucial for dealing with land and energy scarcity issues, said Karl Havard, chief operating officer at Nscale, and could prove “a catalyst for getting renewable energy into the grid”. Nscale plans to spend £2 billion on building data centres in the UK.

Rising geopolitical tensions could give UK-domiciled cloud storage providers like Nscale an edge, Havard said, as “the need to take control of the infrastructure within the sovereign territory” becomes more important.

Earlier this year, European groups raised concerns that the US could use the continent’s reliance on cloud technology provided by US technology companies as leverage in trade talks.

Proximity to the capital means Slough and the broader area just west of London has become the world’s second-biggest data centre hub.

Of all the data transferred in activities, from online shopping and the use of social media to playing video games and streaming TV programmes, by people in London and surrounding areas, nearly half will go through the Slough trading estate.

“It is becoming increasingly un-tenable to build in London,” Kevin Restivo, head of European data centre research at CBRE, the real estate services company, said. He added that people are looking to build data centres in locations they wouldn’t have “dreamed of putting [them] on” even four years ago.